About the expedition

So what is this expedition all about? It really is about understanding deep-sea corals and using them as archives to reconstruct the climate of the past.

Everybody knows about tropical corals. Few people however know that there are also corals that can live in thousands of meters of water depths, and in waters which are very cold. Such corals can form extensive reefs in the dark abyss of the Southern Ocean, and the biologist work very hard to figure out how they actually cope with such extreme environments.

We palaeoclimate researchers however love the cold water corals for another reason. Many species possess a hard skeleton made out of dense aragonite. This skeleton is a fantastic archive for seawater chemistry, and during the life time of a coral, many properties of ambient seawater are recorded in the corals skeleton, just like with a tape recorder. We aim to collect corals that are dead now, and have lived long in the past, during times where ocean chemistry and climate were different than today.

But why do we go all the way to the Southern Ocean to look for them? The Southern Ocean is a key location in understanding glacial/interglacial climate change and the interplay between ocean circulation and atmospheric CO2. It is also one of the most challenging environments in which to establish palaeoceanographic records, and it is heavily undersampled. Pretty cold water corals however thrive down there. During a pilot expedition in 2008 (NBP08-05) we found many corals, fossil and alive, and now we want to go back to map them, capture their habitats in pictures, and collect the fossil ones for palaeoclimate reconstructions.

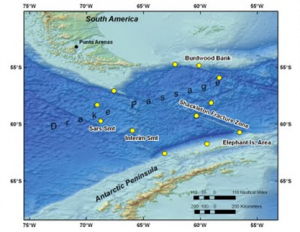

Starting on 9th of May we will work for five weeks on the Nathaniel B. Palmer in the Drake Passage. The Drake Passage is the bit of ocean between South America and the Antarctic Peninsula (55-65°S, 60-70°W), and is widely known for some of the worst weather in the world, and hence its rough seas. I will try to update this blog once a week, but you can also follow our official blog, which all scientists will help to update daily