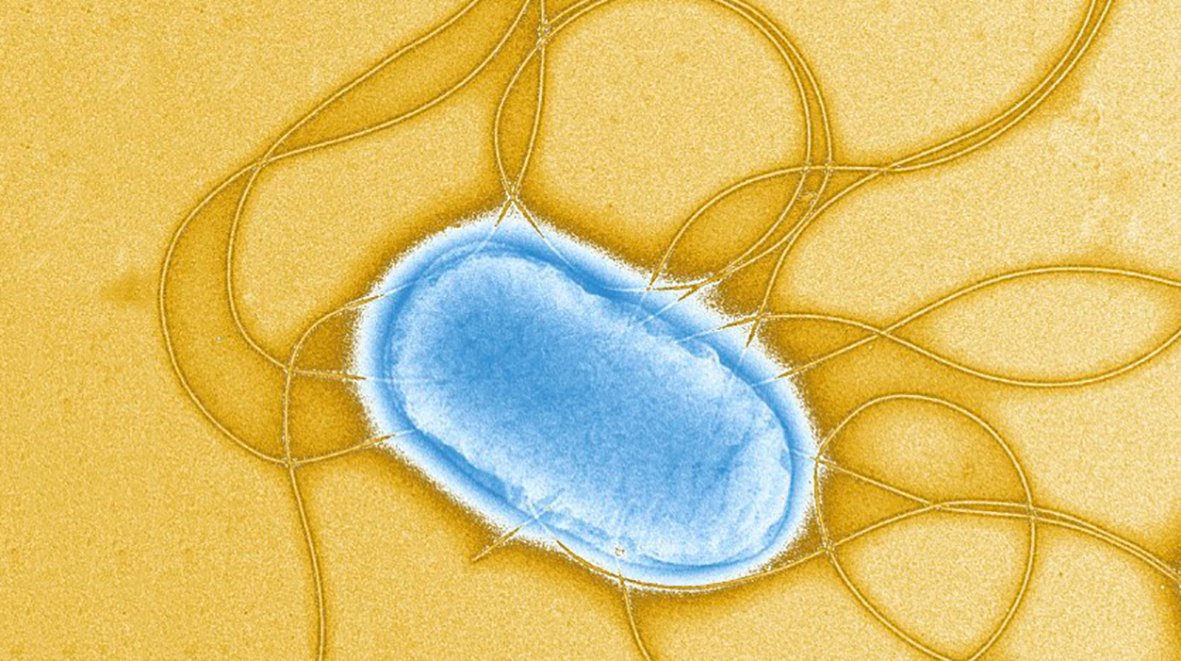

Ahead of the WHO Global Consultation on HTLV-1, Professor Graham Taylor outlines three steps to prioritise the neglected cancer-causing virus.

“I couldn’t do anything for a week after I opened the letter and saw that I was infected with it. I saw H and thought I had HIV. I’d never heard of HTLV”.

It’s not the first time that I’ve heard this, but this was two days ago, almost 40 years since the report in 1980 of the discovery of the human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1). Sadly Janet* is joined in her lack of awareness not only by almost the entire general public but also by most healthcare professionals.

This weekend saw World HTLV Day marked for the second year, with the slogan is: ‘It’s time to care’. This is in response to a general perception that there is a widespread indifference toward HTLV. Hopefully this will change soon. This week, I fly to Tokyo to participate in a WHO Global Consultation on HTLV-1 to address the public health impact and implications of this little-known virus. (more…)