When I got up yesterday morning the labs were emptied out – everybody seemed to be outside. Soon I learned that we were passing by some quite spectacular icebergs. In the photo you can see just one of those bergs. According to our ice specialist Diego Mello we saw bergs of every possible shape, and the excitement hold up for most of the day. If you check out other blogs on the expedition (www.joidesresolution.org) you will see more bergs. The sea has been very calm over the last few days, but the fog prevented more spectacular pictures. Unfortunately the massive presence of icebergs around our first targeted drill site (‘bergy water’ is the term Diego uses) forced the captain to make the decision that drilling on the shelf was not feasible at this point. So the ship turned around and we started heading towards another drill site, more distal from the ice margin, where we arrived this morning. The crew is working very hard to get all ready for drilling and if things go well we should have the first core on deck tonight!

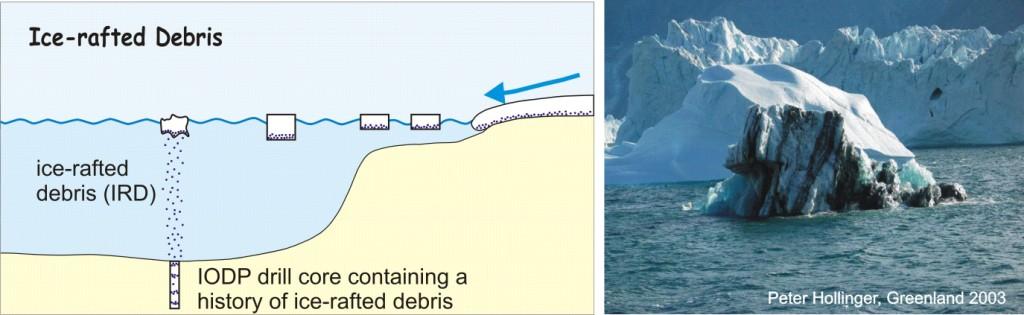

Talking about icebergs is a good starting point to fold in some exciting science we are going to do out here. Icebergs are pretty picture objects, especially when they are all white and shiny. The bergs that I am interested in however are ‘dirty’ icebergs. They carry ice-rafted debris (IRD), picked up from the continents where the icebergs break off the ice shield or outlet glaciers (see schematic drawing).

Most of the Antarctic continent, an area larger than 50 x the UK, is covered by ice. This ice is divided in two distinct units: the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) covering most of the continent, and the roughly eight times smaller West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS). Both ice sheets are separated by the Transantarctic Mountains. Together a water mass is locked up on Antarctica that if melted would be equivalent to a sea level rise of ~60 m. From the study of marine sediments we know that today’s situation on Antarctica with ice cover all over the continent is just a snapshot in the geological history, which has been characterized by the transition from an ice-free “Greenhouse world” more than 40 million years ago, to the present “Icehouse world” with ice caps on both poles. While there is clear signs for present day melting of the WAIS, the EAIS may stay stable for a bit longer. If future temperatures however rise more than a few degrees centigrade from now, there is potential for the large EAIS to become unstable as well. We can study the behavior of this large ice sheet under warming conditions by looking into the record of the past. The most powerful way to do so is to study sediments deposited at the bottom of the ocean –exactly what we try to drill during IODP expedition 318 to Wilkes Land.

I am particularly interested in the record of Ice-Rafted Debris (IRD) around East Antarctica. Studying the layers of past IRD opens a window to explore which parts of the East Antarctic ice margin became unstable under certain environmental conditions. This can be done by matching the chemical signature of IRD from drilled sediment cores with known Antarctic geology. This work is done in collaboration with a team of researchers from Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and Imperial College London. If you want to know more, a paper about the topic is going to come out in the next few weeks in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.