Monday 9 – Thursday 12 February 2015 saw data management and curation professionals and researchers descend on London for the 10th annual International Digital Curation Conference (IDCC), held at 30 Euston Square. Although IDCC is focussed on “digital curation”, in recent years it has become the main annual conference for the wider research data management community.

This year’s conference theme was “Ten years back, ten years forward: achievements, lessons and the future for digital curation”.

Key links:

Day 1: Keynotes, demos and panel sessions

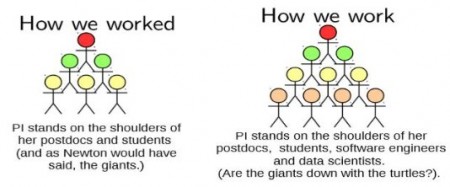

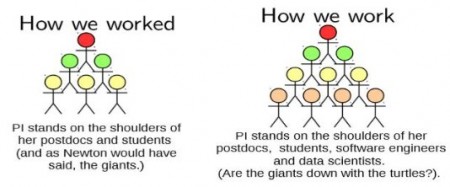

Tony Hey opened the conference with an overview of the past 10 years of e-Science activities in the UK, in highlighting the many successes along with the lack of recent progress in some areas. Part of the problem is that the funding for data curation tends to be very local, while the value of the shared data is global, leading to a “tragedy of the commons” situation: people want to use others’ data but aren’t willing to invest in sharing their own. He also had some very positive messages for the future, including how a number of disciplines are evolving to include data scientists as an integral part of the research process:

Next up was a panel session comparing international perspectives from the UK (Mark Thorley, NERC), Australia (Clare McLaughlin, Australian Embassy and Mission to the EU) and Finland (Riita Maijala, Department for HE and Science Policy, Finland). It was interesting to compare the situation in the UK, which is patchy at best, with Australia, which has had a lot of government funding in recent years to invest in research data infrastructure for institutions and the Australian National Data Service. This funding has resulted in excellent support for research data within institutions, fully integrated at a national level for discovery. The panel noted that we’re currently moving from a culture of compliance (with funder/publisher/institutional policies) to one of appreciating the value of sharing data. There was also some discussion about the role of libraries, with the suggestion that it might be time for academic librarians to go back to an earlier role which is more directly involved in the research process.

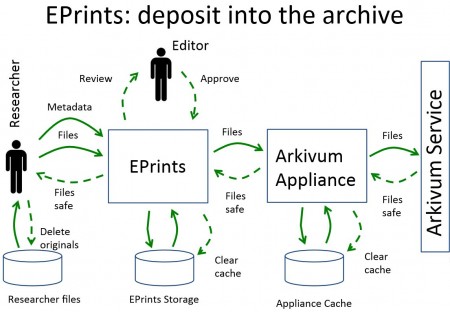

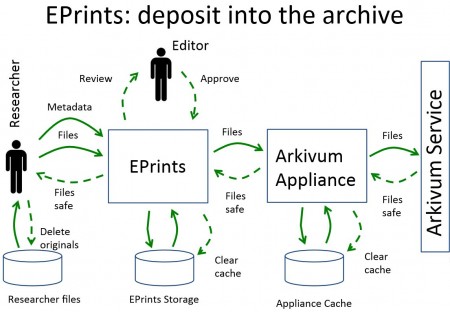

After lunch was a session of parallel demos. On the data archiving front, Arkivum’s Matthew Addis demonstrated their integration with ePrints (similar workflows for DSpace and others are in the works). There was also a demo of the Islandora framework which integrates the Drupal CMS, the Fedora Core digital repository and Solr for search and discovery: this lets you build a customised repository by putting together “solution packs” for different types of content (e.g. image data, audio, etc.).

The final session of the day was another panel session on the subject of “Why is it taking so long?”, featuring our own Torsten Reimer alongside Laurence Horton (LSE), Constanze Curdt (University of Cologne), Amy Hodge (Stanford University), Tim DiLauro (Johns Hopkins University) and Geoffrey Bilder (CrossRef), moderated by Carly Strasser (DataCite). This produced a lively debate about whether the RDM culture change really is taking a long time, or whether we are in fact making good progress. It certainly isn’t a uniform picture: different disciplines are definitely moving at different speeds. A key problem is that at the moment a lot of the investment in RDM support and infrastructure is happening on a project basis, with very few institutions making a long-term commitment to fund this work. Related to this, research councils are expecting individual research projects to include their own RDM costs in budgets, and expecting this to add up to an infrastructure across a whole institution: this was likened to funding someone to build a bike shed and expecting a national electricity grid as a side effect!

There was some hope expressed as well though. Although researchers are bad at producing metadata right now, for example, we can expect them to get better with practice. In addition, experience from CrossRef shows that it typically takes 3–4 years from delivering an infrastructure to the promised benefits starting to be delivered. In other words, “it’s a journey, not a destination”!

Day 2: research and practice papers

Day 2 of the conference proper was opened by Melissa Terras, Director of UCL Centre for Digital Humanities, with a keynote entitled “The stuff we forget: Digital Humanities, digital data, and the academic cycle”. She described a number of recent digital humanities projects at UCL, highlighting some of the digital preservation problems along the way. The main common problem is that there is usually no budget line for preservation, so any associated costs (including staff time) reduce the resources available for the project itself. In additional, the large reference datasets produced by these projects are often in excess of 1TB. This is difficult to share, and made more so by the fact that subsets of the dataset are not useful — users generally want the whole thing.

The bulk of day 2, as is traditional at IDCC, was made up of parallel sessions of research and practice papers. There were a lot of these, and all of the presentations are available on the conference website, but here are a few highlights.

Some were still a long way from implementation, such as Lukasz Bolikowzki’s (University of Warsaw) “System for distributed minting and management of persistent identifiers”, based on Bitcoin-like ideas and doing away with the need for a single ultimate authority (like DataCite) for identifiers. In the same session, Bertram Ludäscher (University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign) described YesWorkflow, a tool to allow researchers to markup their analysis scripts in such a way that the workflow can be extracted and presented graphically (e.g. for publication or documentation).

Daisy Abbot (Glasgow School of Art) presented some interesting conclusions from a survey of PhD students and supervisors:

- 90% saw digital curation as important, though 60% of PhD holders an 80% of students report little or no expertise

- Generally students are seen as having most responsibility for managing thier data, but supervisors assign themselves more of the responsibility than the students do

- People are much more likely to use those close to them (friends, colleagues, supervisors) as sources of guidance, rather than publicly available information (e.g. DCC, MANTRA, etc.)

In a packed session on education:

- Liz Lyon (University of Pittsburgh) described a project to send MLIS students into science/engineering labs to learn from the researchers (and pass on some of their own expertise);

- Helen Tibbo (University of North Carolina) gave a potted history of digital curation education and training in the US; and

- Cheryl Thompson (University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign) discussed their project to give MLIS students internships in data science.

To close the conference proper, Helen Hockx-Yu (Head of Web Archiving, British Library) talked about the history of web archiving at the BL and their preparation for non-print legal deposit, which came into force on 6 April 2013 through the Legal Deposit Libraries (Non-Print Works) Regulations 2013. They now have two UK web archives:

- An open archive, which includes only those sites permitted by licenses

- The full legal deposit web archive, which includes everything identified as a “UK” website (including `.uk’ domain names and known British organisations), and is only accessible through the reading room of the British Library and a small number of other access points.

Workshops

Data Carpentry

Software Carpentry is a community-developed course to improve the software engineering skills and practices of self-taught programmers in the research community, with the aim of improving the quality of research software and hence the reliability and reproducibility of the results. Data Carpentry is an extension of this idea to teaching skills of reproducible data analysis.

One of the main aims of a Data Carpentry course is to move researchers away from using ad hoc analysis in Excel and towards using programmable tools such as R and Python to to create documented, reproducible workflows. Excel is a powerful tool, but the danger when using it is that all manipulations are performed in-place and the result is often saved over the original spreadsheet. This both destroys (potentially) the raw data without providing any documentation of what was done to arrive at the processed version. Instead, using a scripting language to perform analysis enables the analysis to be done without touching the original data file while producing a repeatable transcript of the workflow. In addition, using freely available open-source tools means that the analysis can be repeated without a need for potentially expensive licenses for commercial software.

The Data Carpentry workshop on Wednesday offered the opportunity to experience Data Carpentry from three different perspectives:

- Workshop attendee

- Potential host and instructor

- Training materials contributor

We started out with a very brief idea of what a Data Carpentry workshop attendee might experience. The course would usually be run over two days, and start with some advanced techniques for doing data analysis in Excel, but in the interest of time we went straight into using the R statistical programming language. We went through the process of setting up the R environment, before moving on to accessing a dataset (based on US census data) that enables the probability of a given name being male or female to be estimated.

The next section of the workshop involved a discussion of how the training was delivered, during which we came up with a list of potential improvements to the content. During the final part, we had an introduction to github and the git version control system (which are used by Software/Data Carpentry to manage community development of the learning materials), and then split up into teams to attempt to address some of our suggested improvements by editing and adding content.

I found this last part particularly helpful, as I (in common with several of the other participants) have often wanted to contribute to projects like this but have worried about whether my contribution would be useful. It was therefore very useful to have the opportunity to do so in a controlled environment with guidance from someone intimately involved with the project.

In summary, Data Carpentry and Software Carpentry both appear to be valuable resources, especially given that there is an existing network of volunteers available to deliver the training and the only cost then is the travel and subsistence expenses of the trainers. I would be very interested in working to introduce this here at Imperial.

Jisc Research Data Spring

Research Data Spring is a part of Jisc’s Research at Risk “co-design” programme, and will fund a series of innovative research data management projects led by groups based in research institutions. This funding programme is following a new pattern for Jisc, with three progressive phases. A set of projects will be selected to receive between £5,000 and £20,000 for phase 1, which will last 4 months. After this, a subset of the projects will be chosen to receive a further £5,000 – £40,000 in phase 2, which lasts 5 months. Finally, a subset of the phase 2 projects will receive an additional £5,000 – £60,000 for phase 3, lasting 6 months. You can look at a full list of ideas on the Research At Risk Ideascale site: these will be pitched to a “Dragon’s Den”-style panel at the workshop in Birmingham on 26/27 February.

The Research Data Spring workshop on Thursday 12 February was an opportunity to meet some of the idea owners and for them to give “elevator pitch” presentations to all present. There was then plenty of time for the idea owners and other interested people to mingle, discuss, give feedback and collaborate to further develop the ideas before the Birmingham workshop.

Ideas that seem particularly relevant to us at Imperial include:

Read International Digital Curation Conference 2015 in full