Every student we send abroad has a different story to tell but all of them learn and benefit from the experience. Our students aren’t spending a year on holiday and this cultural report from a student who spent his year in Madrid is testament to the effect their environment can have on them.

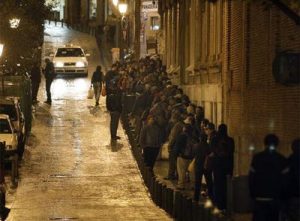

Every morning I make the short walk from my flat on the edges of Malasaña to Sol, in order to catch the train to university. My journey on foot takes me along Gran Vía and through the heart of Madrid’s shopping district. It is an affluent part of the city yet as I pass the still-closed shop fronts and the early-morning cafés, my eyes are drawn to the many doorways containing blanketed figures or the cardboard mattresses of early risers. For the more experienced commuters these unfortunate individuals are the norm, but I often find myself staring. Growing up in Cornwall it felt like there were much fewer overt signs of homelessness despite the fact that the region, and especially the town of Redruth where I live, in fact has the second highest level of homelessness in the UK behind Westminster. Even my last two years spent studying in London, where the sight of rough sleepers is by no means uncommon, have not prepared me for the numbers of people who sleep on the streets of Madrid each night.

The last survey of the city found that more than 1900 people were homeless in Madrid, 1141 were spending the night in shelters and more than 700 were sleeping rough. This number is roughly equivalent to statistics for London but in a city which is three times smaller in terms of area and population it represents a much greater problem. Levels of homelessness have risen sharply across Europe since the financial crash of 2008 and Spain has been one of the countries worst hit. In Madrid alone the numbers sleeping on the street on any given night has risen by more than 35% in the last 5 years and the same changes have been seen in Barcelona and other cities.

The institutions tasked with monitoring homelessness admit that understanding the exact numbers of people sleeping rough in a city is a nigh-on impossible task. Most estimates come indirectly from the number of individuals interacting with organisations set up to aid those in need. This most recent survey of Madrid, which was conducted by Samur Social (an ambulance- like emergency social service run by the municipal government), took a different approach: a team of over 700 volunteers, in the most part university students, was sent out to cover the city; observing, recording and where possible interviewing all the individuals they encountered. The result of this exercise is a report which contains far more than just a series of facts and figures, it conveys something much more personal. Rather than arbitrarily grouping answers into predetermined categories, verbatim responses were recorded which gives parts of the document a conversation-like feel. The beauty of the verbatim responses is that they also allow the reader to get a feel for the individuals on the street, who they are, how they are feeling and their opinions on possible causes and solutions for the crisis on the streets. A particularly powerful section of the survey asked users about their hopes for the future. The answers range from inspiring: “To live, to live well and for others to live well too”, to simple: “To have a garden and tend to my fruit and vegetables”, to thoroughly depressing: “I will die in the streets”.

I will not recount here all the findings of the report, which can be accessed online, instead I will talk about some which struck me as I read through the document and which tally with my personal experience and observation. The first of these is the age structure of the homeless population; the majority are between thirty and fifty but almost 15% are over 60 and 10% are around my age or younger. I have been really shocked in my time here to see the elderly and very young with nowhere to live. FOESSA, an organisation which monitors social exclusion across the whole of Spain has found that the the number of individuals suffering from severe social exclusion has been growing fastest amongst the under thirties and especially the under eighteens over recent years. This has a clear link to the devastating level of youth unemployment in the country, a problem which I have found to be on the mind of all the young people I meet in Spain; even amongst my colleagues at Autonoma, one of the most prestigious universities in the country.

It was interesting to note the ethnic mix of the homeless population investigated, I was surprised to see that only 44% were found to be of Spanish origin. 60% of the immigrant population in the streets were from eastern European states, a trend which is mirrored in many countries in the west of Europe. These migrants, attracted by the strength of the western European economy are part of a movement that has continued since the incorporation of these nations in to the European Union. Many here are from Romania, a country with which Spain has many cultural and religious similarities. More unique to Spain is the large population of migrants from the Magreb and sub-Saharan Africa. This is a result not only of Spain’s proximity to the north of Africa but also of high levels of migration into the Spanish exclaves of Melilla and Ceuta which border Morocco. For these individuals and for so many others like them the prospect of a better life has proved false.

The impact of the recent refugee crisis in the Mediterranean is not yet fully understood but has certainly not been as severe as in Italy or Greece. Spain has agreed to accept roughly sixteen thousand of the most recent refugees and the Palacio de Cibeles, headquarters of the local authority, proudly displays a “Refugees Welcome” sign. This country has been remarkable in that there is a conspicuous absence of the far-right parties which have sprung up in many other parts of the E.U.. In an excellent article for El Pais, Ana Carbajosa has laid out some of the possible reasons for this, citing the country’s recent history of fascist rule and emigration.

Another interesting aspect is the presence of individuals from other EU-15 states who make up 10% of immigrants on the streets. For several weeks at the beginning of my time here, I passed the same man sitting quietly, surrounded by bags, outside El Corte Inglés, Madrid’s luxury retailer. One morning I was surprised to hear him talking on the phone with an English accent. That evening on the walk home, as I handed him some change, I asked him how he had come to be living on the streets so far from home. He told me that he had been homeless in the UK but had decided to travel to Spain to take advantage of a more hospitable climate and a friendlier public. When he arrived he met a Spanish woman who was also living rough and they had stuck together ever since. He also told me of several other British ex-pats he knew who had come to Spain in better times with jobs and houses but had been forced on to the streets when the property bubble burst. I still see the man regularly on my walk into town and often stop to chat with him or his friend who by a curious chance is also studying for a biology qualification.

The causes of ‘sinhogarismo’ are manifold and the government’s slashing of social housing spending is not the least of them, but in Spain the key driver has been the plummeting number of jobs. The unemployment rate in Spain currently stands at 20.9% and amongst under twenty fives, it is running at over 45%. The situation is somewhat better in the capital where the economy is more prosperous yet many people are still out of work. When huge swathes of the population lost their jobs they also lost their ability to keep up with rent or mortgage payments. It has been reported that since the crisis in 2007 there have been over 600000 mortgage foreclosures and the most recent statistics say that 70000 eviction proceedings were brought to court in 2014. In this way the problems in Spain differ from those facing the United Kingdom, we face a chronic shortage of affordable housing stock, especially in densely populated areas like London. In comparison Spain has an astonishing 3.4 million homes which currently sit empty, to put this figure into perspective, it is thought that there are currently 4.1 million people homeless across the whole of Europe.

Problems faced by Madrid’s homeless

The homeless of Madrid face are much more likely to be victims of crime than other citizens. Of the respondents to the Samur Social survey more than 50% said that they had been a victim of crime and more shockingly many said that they felt they had been targeted for such crimes precisely because they were living on the streets. Many homeless individuals fear interacting with government officials and have a deep-seated mistrust of the police, for this reason many will never report incidents, further increasing their vulnerability. Homeless people are not just victims of crime however, the desperation of their situation often drives those without homes to commit petty offences: theft, street vending and drug dealing. This has a detrimental effect on an individual level, as prosecution and possible incarceration increase levels of social exclusion. It has broader societal impacts as well and indeed some have begun to see the homeless as the cause of many of Madrid’s problems rather recognising them as what they truly are, symptoms of wider issues. One mayoral candidate and prominent politician in the Partido Popular went as far as to propose clearing homeless people from the centre of the city and making it illegal to sleep in the streets as a means to boost tourism in the capital. The idea was roundly rejected by NGOs and volunteers as impractical, illegal and unethical.

Staying healthy is a major concern for everyone living on Madrid’s streets. The report suggests that more than 40% suffer from some sort of ongoing health problems and of these only a quarter are taking med- ication or receiving treatment. It is heart-wrenching to see people with extreme physical disabilities living and sleeping on the streets and al- though the climate may be more gentler here than in some other European countries, a winter spent

outdoors presents a real threat to anyone. In Spain, as in many countries, the issue of addiction and homelessness is ever present. Alcohol and drug dependencies are disproportionately rep- resented amongst individuals who sleep rough and in many cases have been a key factor in the process which has brought these individuals to the street. This makes many people fear that by donating to seemingly needy individuals they are merely funding unhealthy or illicit behaviours. Research by the National Institute for Statistics indicates that, although this statement may hold some truth, alcoholism and drug addiction are by no means endemic and in the responses to the Samur Social survey most individuals who had substance abuse issues were desperate to get treatment in order to help them get back on their feet. It is widely accepted by the organisations tasked with rehabilitation that the system, in it its current form, is failing these individuals.

Current support mechanisms

In Madrid, and all around Spain, there are many brilliant organisations aiming to help im- prove the lives of the homeless and where possible to try to get them off the streets and into some form of accommodation. Some are run by the state, others are non-governmental, the church in Spain also plays a key role in caring for individuals. In Madrid the municipal government response to the crisis has two prongs; Samur Social which acts as an emergency service fulfilling many functions. It has mobile teams which act alongside ambulance teams, telephone support centres for advising those at risk of social exclusion and coordinates responses between other branches of the government and emergency services. The second element of the government response is the three open centres which are run to provide temporary accommodation (just over 500 places total) and health and hygiene facilities to those in need.

The two largest NGO’s involved with the assistance of homeless individuals are Fundacíon RAIS and Solidarios. RAIS is a charity set up by a group of social service professionals more than 15 years ago, which runs all manner of projects from emergency accommodation and day centres to work placement and training schemes. It began its work in the region of Madrid but it opera- tions have now spread to encompass many areas of Spain where homelessness and social exclusion are a problem. Solidarios is a somewhat different organisation set up by a professor from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid more than 25 years ago. It aims to train and organise volunteers to supervise multiple projects simultaneously. It currently coordinates many schemes and works with the homeless, the elderly and ex-convicts among other vulnerable groups. There are numer- ous other smaller charities running in the city for example, I have recently signed up to volunteer with a charity called Serve the City, which has been set up by a group of UK ex-pats in Madrid to allow foreign citizens to participate in various social schemes such as running sports events with at-risk young people and keeping elderly people company in day centres. The main church-run organisation in the city is the Spanish branch of Cáritas, an international confederation of Catholic charities. It offers a wide range of services; day to day care of needy individuals, temporary accommodation for periods of one night to six months as well as services to help homeless individuals deal with administrative processes and to re-enter the world of work. Along with Cáritas there are large number of other smaller ecclesiastical institutions offering services to the needy.

What can be done?

Over the last two years Spain has seen some of the strongest economic growth in Europe (3.8% in the last fiscal year), unemployment has also fallen sharply. To the ire of many, Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy even went as far as to declare Spain’s crisis over, only to quickly retract the statement when he was reminded that more than 4 million people lack employment. Nonetheless the improvement of Spain’s financial fortunes will no doubt go some way to ease the burden on many people currently at risk of losing their homes or jobs. It is less clear what the effect on those who have already been forced onto the streets will be, some people have been quick to note that although many economic indicators have improved, the numbers of homeless have increased rather than fallen. It is well known that the step down to the streets is a very difficult one to reverse; the stigma attached to the imposition as well as the administrative problems which go along with lacking a permanent address are a serious hindrance for anyone seeking to return to employment. For this reason, RAIS has launched a new initiative, H ́abitat, which is based around the established concept of ‘Housing First’. The premise of this concept, which was developed in the 1990’s, is that as permanent living space is what the homeless principally lack, providing it rapidly should be the key priority of any support system. Other goals such as social integration and employment can more easily be achieved from a permanent home. This model has great potential in Spain as the housing stock is available to be filled and there is great hope for the scheme.

Non-governmental organisations are leading the way in tackling these issues in Spain currently, but they do not have sufficient resources to con- tinue spearheading the campaign. In reality their true function should be to support and complement government initiatives and here lies the crucial problem in the country, a severe lack of state investment. Since 2013 spending on social services has fallen by 34% as part of ruthless austerity measures. The country is now moving slowly towards recovery and so this downward trend must be reversed. Last December general election results were inconclusive, the incumbent conservative government, Partido Popular (PP) gained 28% of the vote with the socialist PSOE in second with 22%. The big story of the election was the rise of two new parties, Podemos which gained 20% and Citizens (13%). In particular, the rise of Podemos has given many hope; the party was formed by a group of academics and professionals in Madrid and is led a by former Complutense lecturer, Pablo Iglesias. It campaigned on a progressive, anti-austerity platform and it has been likened to Syriza, its ally in the European Parliament.

Since the polls, no effective coalition has been formed and the political system remains in deadlock which can only be a bad the thing for the country as a whole and for the homeless especially. The buzz of excitement I sensed when listening to conversations pre-election has been palpably numbed by a period of intense squabbling as the parties vie to form a government. With regards to homelessness, the stances of the two traditional parties, PP and and PSOE, have not shifted greatly in response to the changing political landscape and some feel that their policies are tired and will do nothing to solve the current crisis. Podemos has argued forcefully on this subject and a central policy of their campaign was a radical proposal for a universal basic income of €650 which would go a long towards solving some problems faced by the homeless. The opposition has derided the scheme, and it is no doubt ambitious, but it has been hailed by NGOs and by the public as the kind of refreshing thinking which Spain needs in order to tackle rising inequality. Other schemes included in the manifestos of the key parties have been the ending of laws which make the occupation of empty or abandoned building illegal and the possibility of compulsory purchases by the state to create more social housing.

There will be no easy path back to a fairer society for Spain; it will require work and belief from the government, the charity sector and the public. Some lessons must be learnt from the failings of the past and others should be taken from the success stories of other countries such as Denmark where in some regions homelessness has been halved in recent years. I have said that I was shocked when I first arrived in this city and saw the destitute individuals living rough and I am still, however having read of, and seen, the action of the city’s volunteers and workers, I am not totally disheartened and I hope that with time, fewer and fewer people will have to call the streets of Madrid home.

Reading List

- Muñoz, M., Sanchez, R. and Cabrera, P. VII Recuento de personas sin hogar. 11/12/2014. Available from: http://www.madrid.es/UnidadesDescentralizadas/ IgualdadDeOportunidades/SamurSocial/NuevoSamurSocial/ficheros/DATOS%20VII% 20RECUENTO.pdf (Accessed 21/01/2016).

- Combined Homelessness and Information Network. Combined Homelessness and Information Network. London, 06/2015. Available from: https://files.datapress.com/ london / dataset / chain – reports / CHAIN % 20Greater % 20London % 20full % 20report % 202014-15.pdf (Accessed 03/02/2016).

- Department for Communities and Local Government. Rough Sleeping Statistics England – Autumn 2014 Official Statistics. 26/02/2015. Available from: https://www.gov. uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/407030/Rough_ Sleeping_Statistics_England_-_Autumn_2014.pdf (Accessed 28/01/2016).

- Fundación FOESSA. VII Informe sobre exclusión y desarrollo social en España. Madrid. Available from: http://www.foessa2014.es/informe/uploaded/descargas/VII_ INFORME.pdf

- Fundación FOESSA. Informe FOESSA. Available from: http://www.foessa2014.es/ informe/ (Accessed 23/01/2015).

- Neate, R. ‘Scandal of Europe’s 11m empty homes’. In: The Guardian. Society (23/02/2014). issn: 0261-3077. Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/society/ 2014/feb/23/europe-11m-empty-properties-enough-house-homeless-continent- twice (Accessed 10/02/2016).

- Volker Busch-Geertsema et al. Extent and Profile of Homelessness in European Member States. Brussels, 12/2014. Available from: http://feantsaresearch.org/IMG/pdf/ feantsa-studies_04-web2.pdf (Accessed 18/01/2016).

- Ana Carbajosa. Why Spain has resisted the rise of the far right. El Pais. 15/07/2015. Available from: http://elpais.com/elpais/2015/07/06/inenglish/1436183846_ 250471.html (Accessed 27/01/2016).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Tasas de paro por sexo y grupo de edad. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 01/2016. Available from: http://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla. htm?t=4086 (Accessed 23/01/2016).

- General Council of the Judiciary. The Spanish Judiciary in figures: 2014. 24/07/2015. Available from: http://www.poderjudicial.es/cgpj/es/Temas/Estadistica- Judicial/Analisis-estadistico/La-Justicia-dato-a-dato/La-justicia-dato-a- dato–ano-2014 (Accessed 12/02/2016).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta a las personas sin hogar. 21/12/2012. Available from: http://www.ine.es/prensa/np761.pdf (Accessed 02/02/2016).

- Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Ayuntamiento de Madrid. 2016. Available from: http://www. madrid.es/portal/site/munimadrid

- LARES. Estrategia municipal para la prevención y atención al sinhogarismo, 2015-2020. 04/2015. Available from: http://www.madrid.es/UnidadesDescentralizadas/ IgualdadDeOportunidades / SamurSocial / NuevoSamurSocial / ficheros / LARES . %20Estrategia%20Municipal%20erradicaci%C3%B3n%20sinhogarismo%202015-2020. pdf

- Cáritas Española. Nadie sin hogar 2014. Campañas de sensibilización. 11/2014. Available from: http://www.caritas.es/qhacemos_campanas_info.aspx?Id=788 (Accessed 08/01/2016).